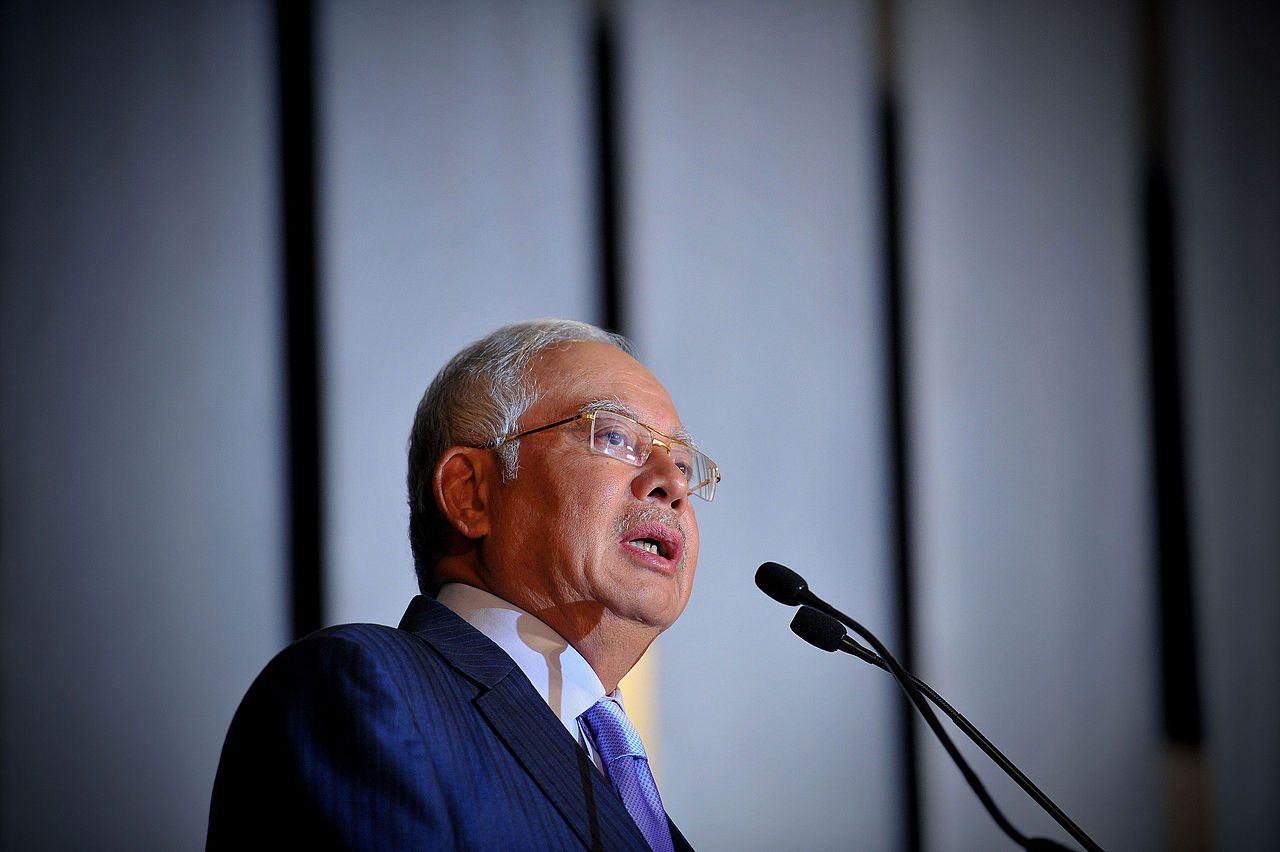

On January 19, Malaysia hosted the Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Kuala Lumpur for an Extraordinary Session on the situation of the Rohingya. Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak urged the government of Myanmar to end the humanitarian tragedy and subsequently pledged US$2.2 million to aid the minority group. In a final communiqué, the OIC called upon Myanmar to resolve the root of the crisis in Rakhine State, among other calls to action, and reinstate the citizenship of the Rohingya. The request was also made for the government to allow a high-level delegation from the OIC to travel to Rakhine State in order to conduct an independent inquiry. Such access is unlikely to be granted as travel into the state is still severely restricted.

The meeting was immediately denounced in a press release issued by Myanmar’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The session was deemed “regrettable” and only served to make “a complicated issue worse.” Vocal in its growing discontent of fellow ASEAN member interfering in domestic affairs, the government described Malaysia’s actions as exploitative and promotive of certain political agendas—entirely disregarding the reality that the Rohingya crisis is also an international issue as refugees are fleeing to seek sanctuary throughout parts of Southeast Asia.

In its defense against accusations that it is not taking appropriate measures in resolving the conflict, the Myanmar government cited the creation of two commissions that are helping to find a solution—a claim that is deceptive and contentious. The two commissions established to investigate the abuses occurring in Rakhine State are one thirteen-member group headed by Myanmar Vice President U Myint Swe, and one nine-member Rakhine Advisory Commission headed by former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Despite examining allegations of human rights abuses in the same region, the initial findings of both groups have been polarizing and incongruous.

The interim report released by Vice President Swe’s commission found “insufficient evidence” of rape and violence perpetrated by Myanmar security forces. Allegations of genocide and crimes against humanity were also denied. The report is in stark contrast with Annan’s preliminary statement in November 2016 after visiting Rakhine State. Annan stated:

“As Chair of the Rakhine Advisory Commission, I wish to express my deep concern over the recent violence in northern Rakhine State, which is plunging the State into renewed instability and creating new displacement. All communities must renounce violence and I urge the security services to act in full compliance with the rule of law.”

Annan’s commission has yet to release a full report on its findings, but will do so within 12 mend onths of the commission’s creation—presumably before August 2017.

The decision of the Myanmar government to criticize a meeting held only to alleviate the suffering of a persecuted group is both disappointing and evident of its unwillingness to admit atrocities against the Rohingya are occurring. If the Myanmar government was truly dedicated to ending the crisis in Rakhine State, this Extraordinary Session would have been welcomed and revered, not disparaged. The reduction of conflict and violence can only happen through cooperation, not condemnation.